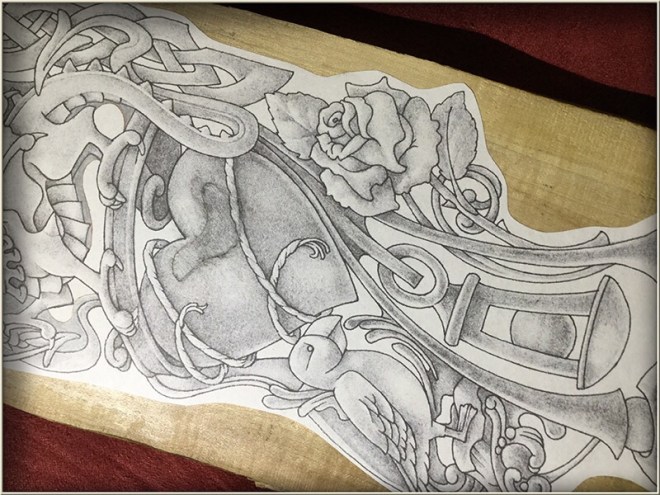

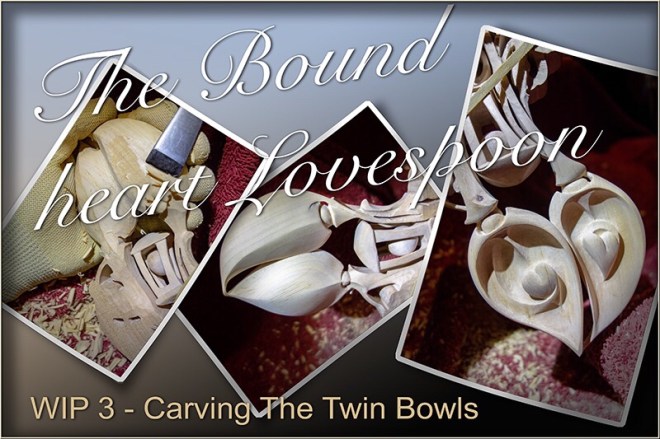

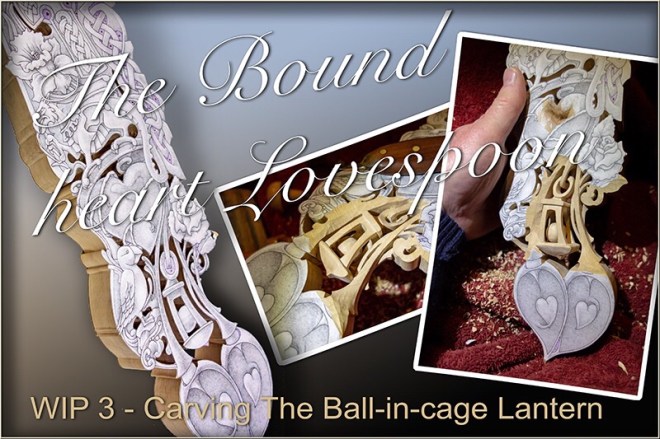

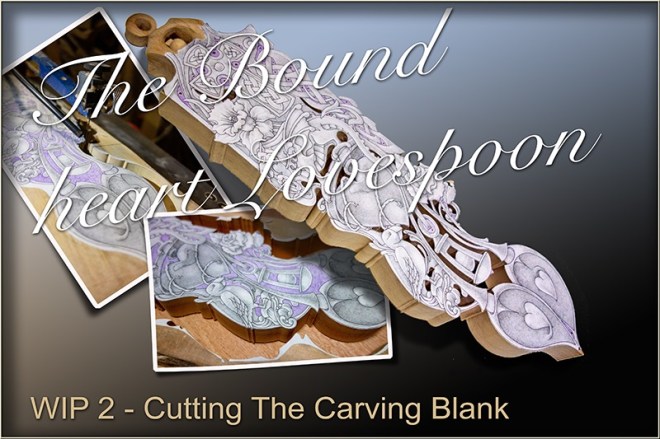

In preparation for yet another attempt at making more regular posts on this blog in this new year, I will wind up the description of the carving and finishing processes used in the bound-heart lovespoon.

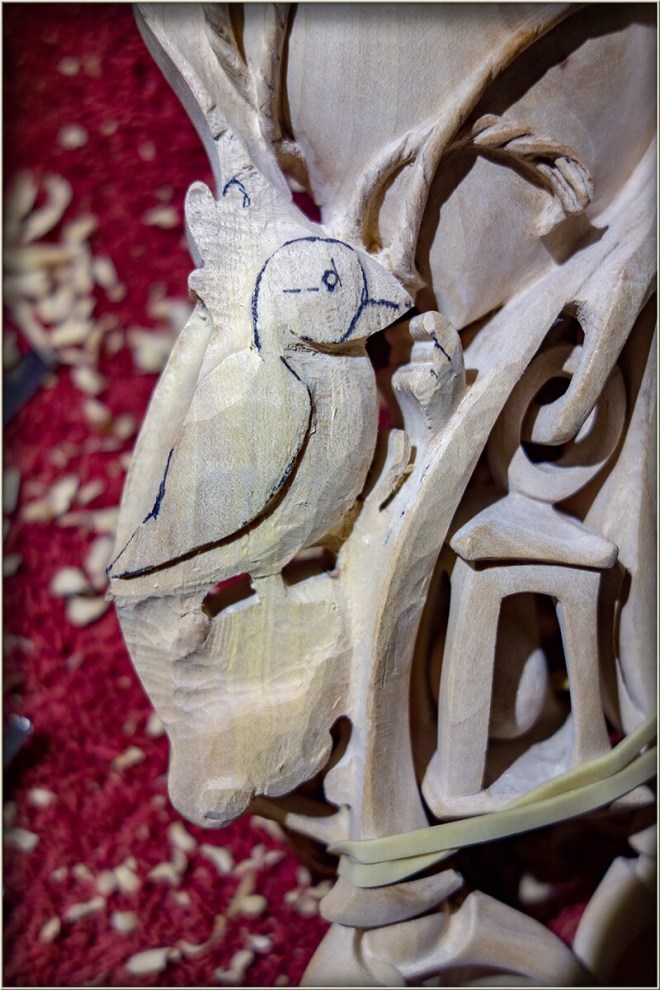

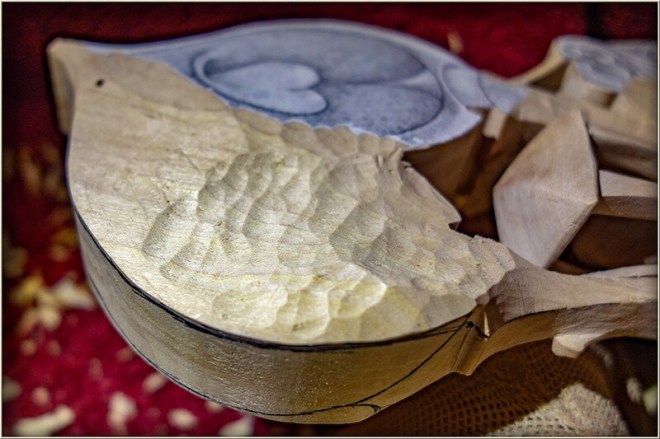

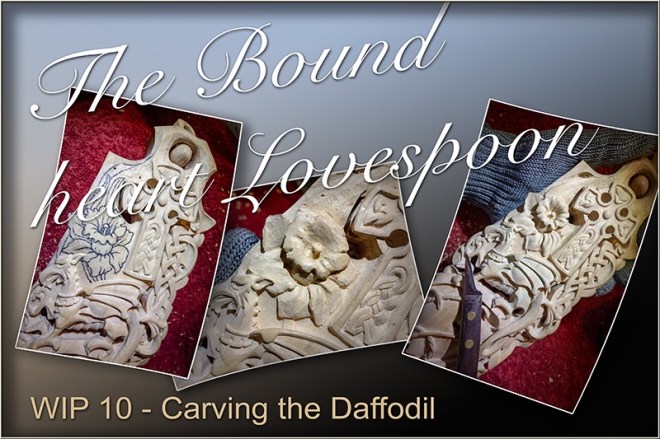

Carving the daffodil motif, begins with drawing the main shapes on the prepared area. Some indication of the lines that will link behind the leaves into the top area of the spoon where the swivel inserts is also made so that this area might be organically related to the various elements as the whole takes shape.

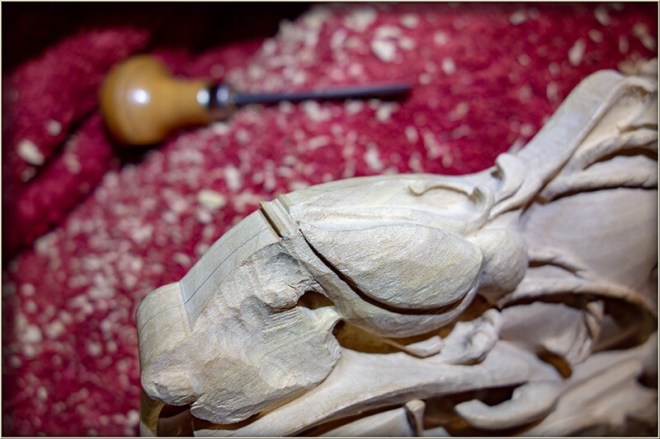

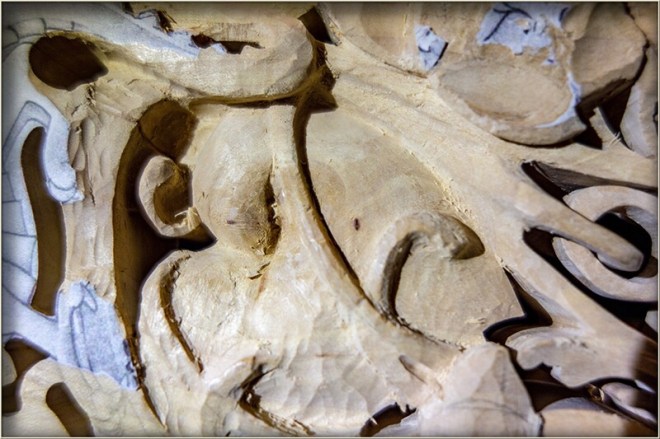

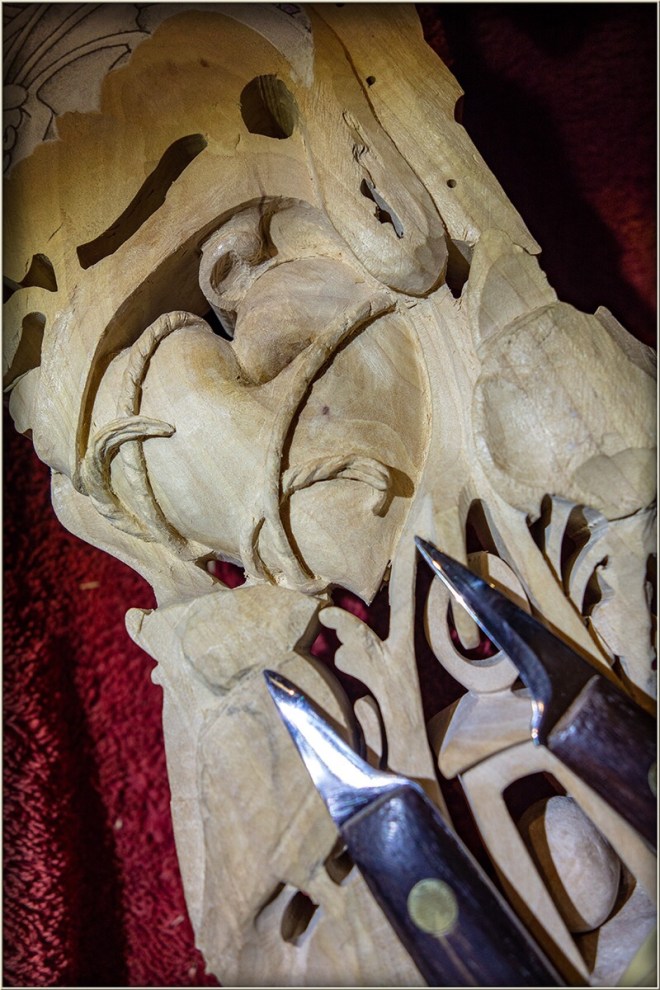

Gradually stop cuts are made along these boundary lines using micro-chisels, working in small increments or various gouges that happen to fit the curves of the lines. Flat gouges making slicing cuts up to these stop cuts enable the timber to be removed down to the necessary levels. The raking light of a properly positioned light source provides descriptive shadows of the forms as you progress to ‘draw’ the dimensional aspects with the projected shadows that are produced.

Above are some of the micro-chisels made from piano wire, that can be used for fine detail areas.

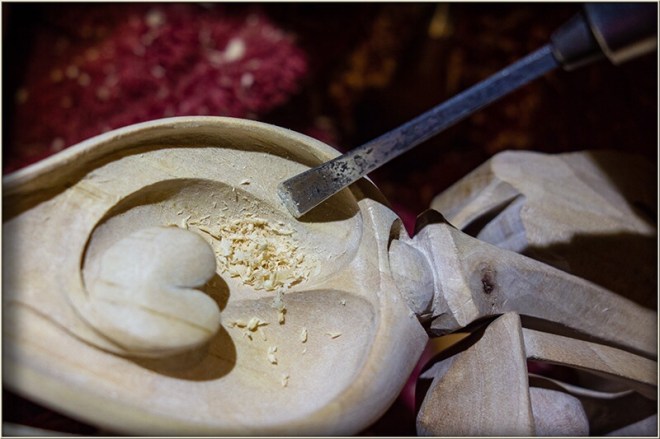

As the levels of each flower part are reached the roundness of their forms can begin to be shaped. The shear depth of a daffodil flower makes it a difficult subject to carve in a Lovespoon where the motifs have been carved in high relief.

It proves to be quite a balancing act when carving something with such natural depth, to ‘flatten’ the form sufficiently for fitting to available dimensions, retaining a relatively undistorted appearance when viewed from a variety of angles, as a Lovespoon invariably is, and not deviating conspicuously from the depth of relief established in the rest of the design. This requires proceeding cautiously and yet boldly at the same time. The necessary caution can’t be allowed to ‘stunt’ the final forms into a timid, half-way-there result. The required caution should be a matter of pace not extent.

The structure of the pistils is gradually established by carving deeply into the flower trumpet while also producing the internal fluting detail on the interior sides. Likewise the topology of the petal surfaces can be detailed and given form by using a micro chisel to trace definite vein lines radiating and curving from the base of each petal.

A ‘veiner’ gouge would be the traditional tool to use for this but I find it safer and more positive at this scale to use stop cuts along the lines and then go in to carve mounds and hollows along the lines. This way you also have the option of transitioning along the vein line from a broad rounded groove to a steep crease where two convex mound walls touch near the base of the petal.

While the form of the daffodil is taking shape the leaves above it and the flowing lines that lead up to the top of the spoon enclosing the swivel are blended into the larger design.

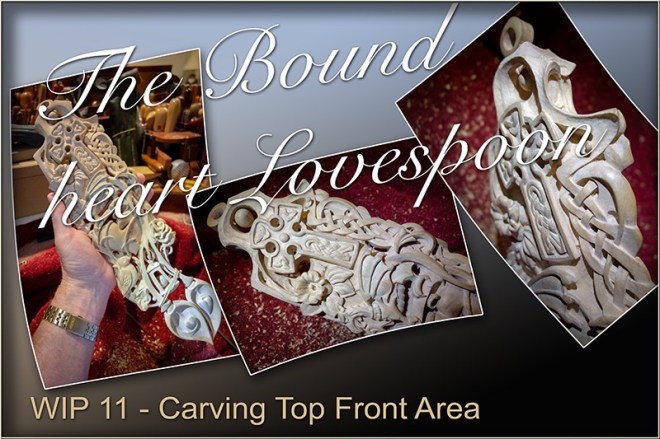

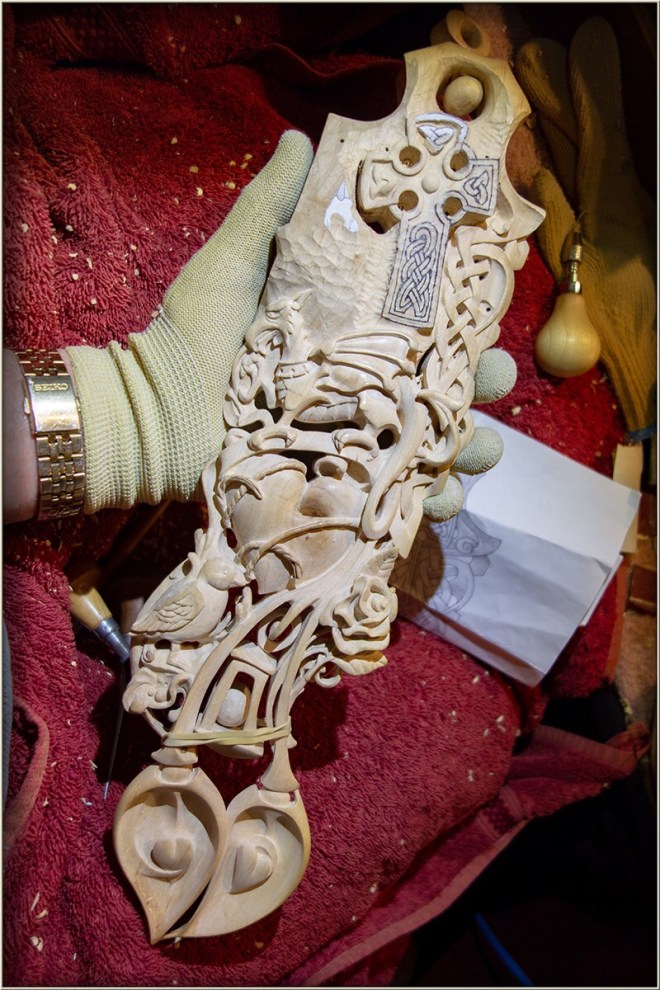

With all of the motifs now completed on the front of the Lovespoon it is time to commence work on the back of the Lovespoon and return to the front for refinement later.

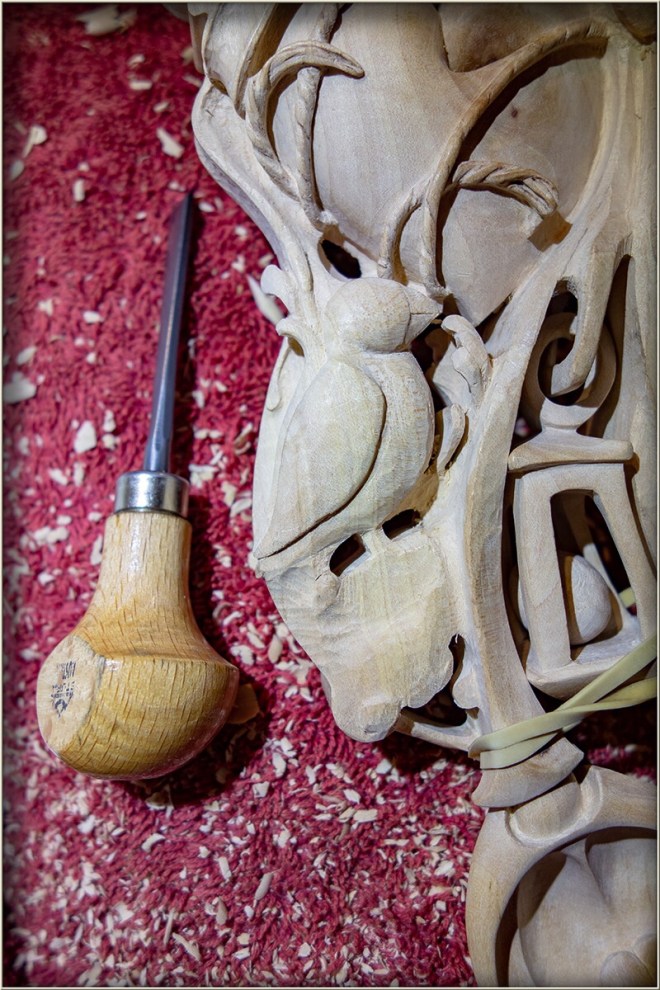

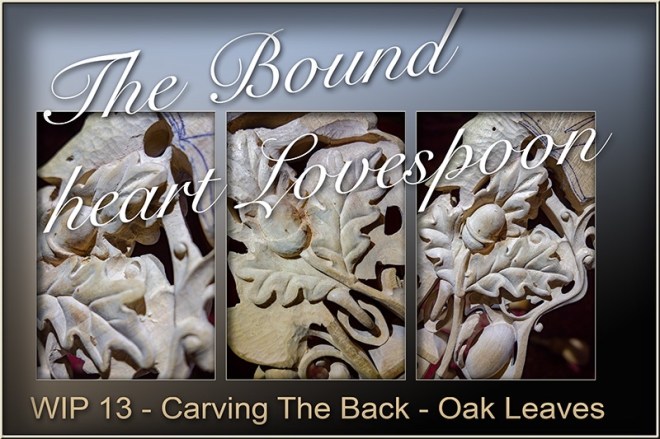

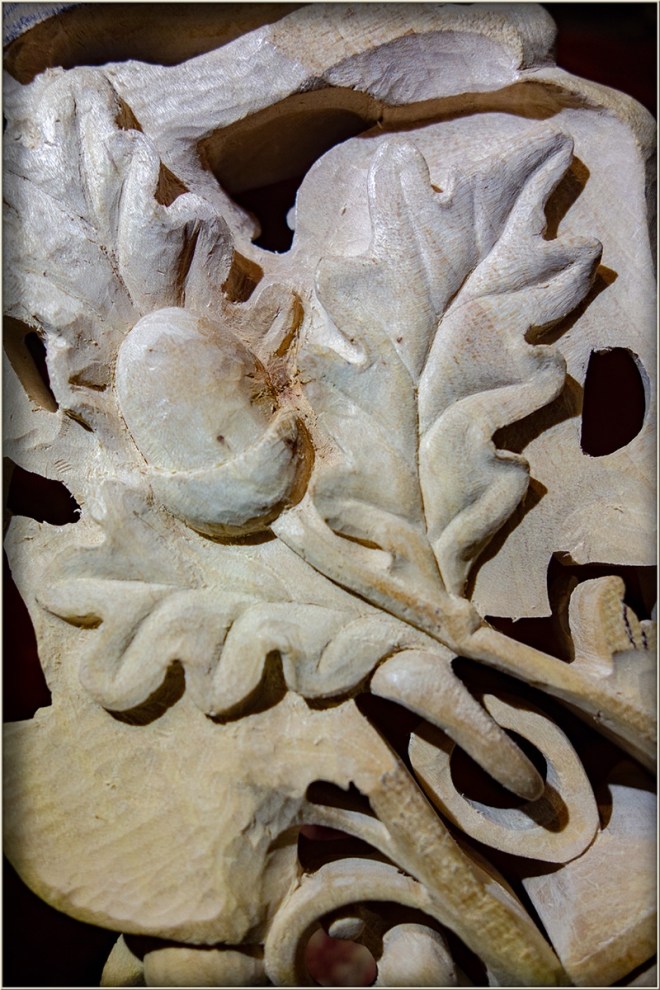

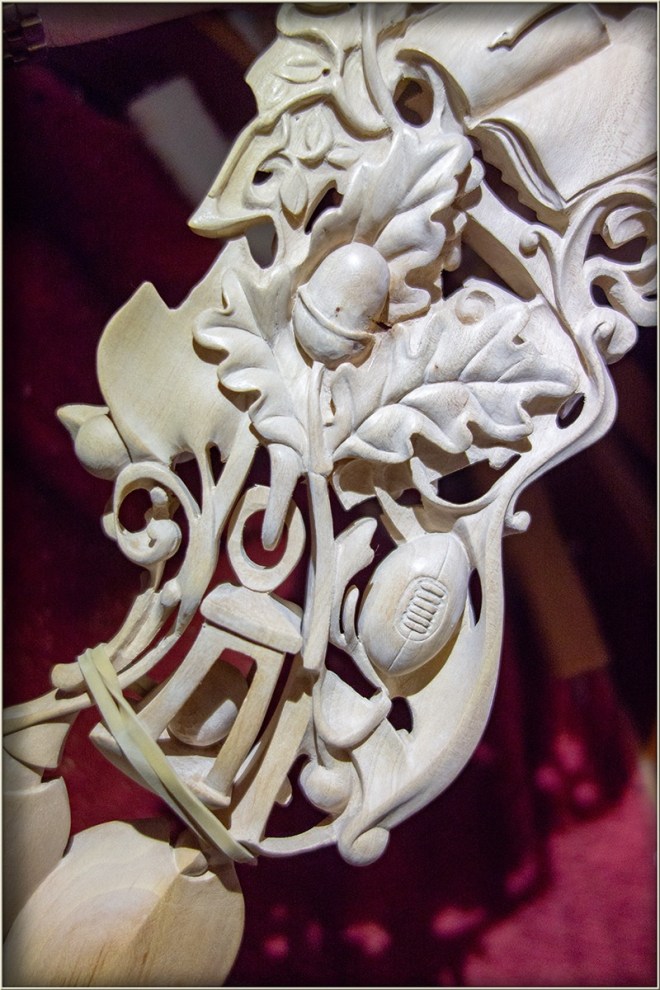

After marking in the various motifs to be carved on the back of the lovespoon, and then after some of the relative levels have been established, at least, partially, the first element to be brought close to its final form is the group of oak leaves and acorn.

The usual procedure has been followed – Stop-cuts along bounding lines of the constituent shapes and forms and then removing material to create those forms. The veins of the oak leaves are all shown as steep creases where the lobe-like sections of the leaves touch with a quilt-like effect, and so using stop cuts along the vein lines seems the best approach.

As the carving proceeds the forms are gradually given enough depth with descriptive shadow, to suggest a little refinement in their individual character. Even in the process of getting each leaf and the acorn properly located at their various levels, it may be that some of this ‘pre-emptive’ detailing will become redundant and be removed when more important overall or global design considerations dictate a change, perhaps in level, shape or inclination.

But this is the nature of what is still, a design process that happens to be developed in tandem with making. Intuitively finding its way amid the emerging forms tossed up in the wake of a keen cutting edge. I am not sure if rotary tools also facilitate this but it is the clean intersecting facets made by sharp tools that I find to be beckoning their use, now or later, for the adding of interest to the forms they work toward.

While this way of working is far from practical or efficient in, a utilitarian sense, it has to be remembered that lovespoon carving is not a practical or potentially lucrative art form, it is pre-eminently a labour of love. I can imagine that someone with decades more experience than I have, might use the same ‘impractical’ process in a manner approaching efficiency but with the resultant work being the most important thing, I must use the resources I have, even if they are only time and stubbornness.

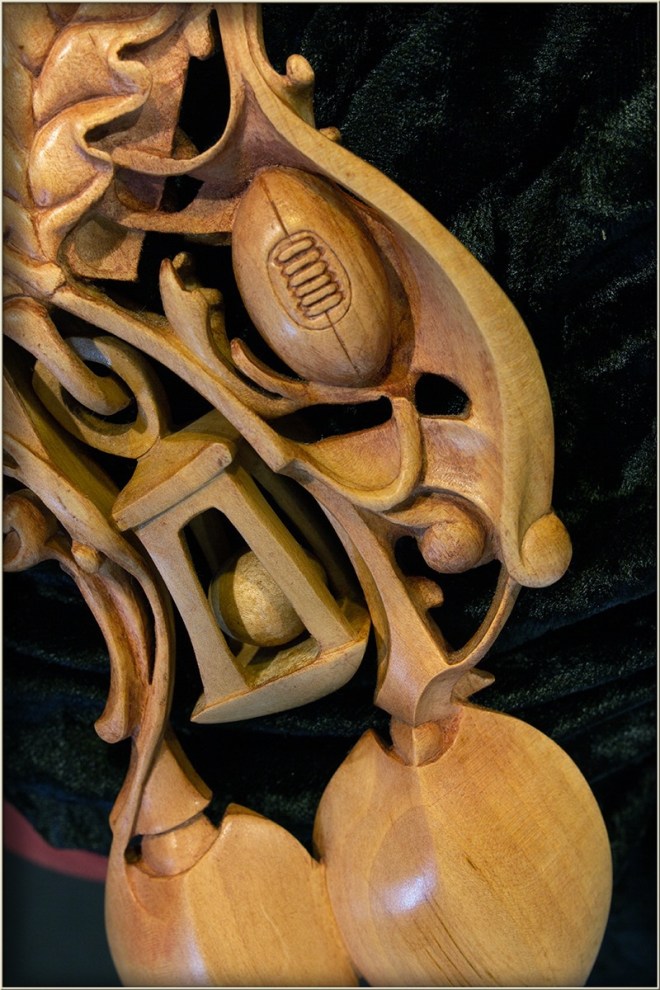

With the oak leaf and acorn forms established, the background art nouveau lines are indicated and some of the other motifs, like the rugby ball plus the book and quill are drawn in and partly shaped. While sharp edge tools are so useful especially in their suggestive results already mentioned, it is files, rasps and scrapers of various kinds that are useful to do the best job when clearly defined less organic forms are being worked. Forms like the rugby ball for example need smooth and accurate shaping. Flat files and rasps in particular lend themselves to shaping smooth convex surfaces like these. Next we will turn our attention to the carving of the book and quill.

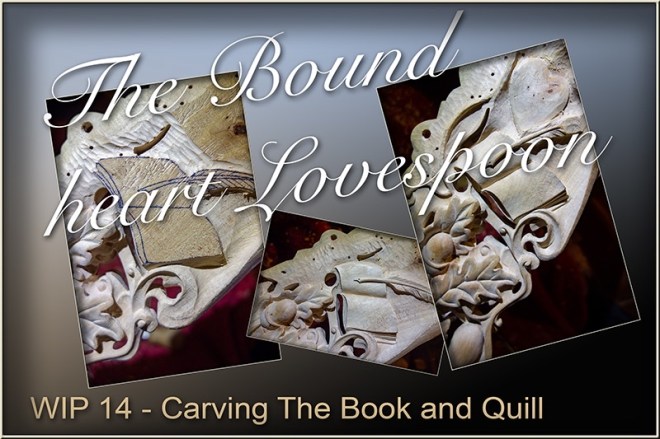

As usual the first task in carving the book and quill will be to establish levels by using stop-cuts and shallow gouges to remove the material up to the boundary wall they form. Sometimes when the bounding lines of the form are relatively un-interupted smooth lines, a small deep gouge can be used to remove the material up to and around them without tediously stabbing shop cuts around the whole outline

In this way the book and quill are outlined and material is removed around them until reaching the lowest level upon which the book rests. Now the quill can begin to take form and the upper surface of the book pages established. From here the more detailed forms are worked forward incrementally.

There is a heart shape to emerge above the book and quill, together with some abstract passages of slow curves melding the motifs with the overall design. In this case the top of the quill had to be reworked to take it to a lower plane and allow a fairer and more natural flow of the book page surface below it.

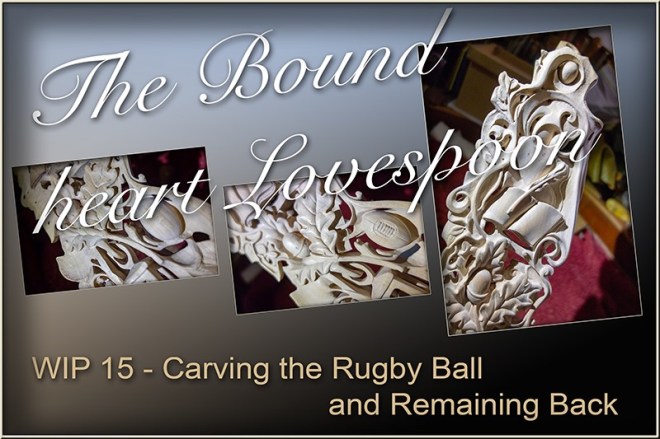

Before finessing the details of the book and quill motifs we will turn our attention to the rugby ball below the oak leaves.

With the basic form of the rugby ball already worked, the details can be worked upon its surface after first drawing them in. The details to be added are the lines that form the ball panels and the lacing on the top.

A more antique style of rugby ball with its leather panels and an inset section enclosing the lacings, less proud of the ball’s surface, than they would be without that inset section, serve more than just increased interest and detail in the simple ovaloid form of the ball.

The more detailed style, happily, reduces the amount of work that would otherwise be needed. This is because, reducing the level across the entire form would be necessary to reveal the lacing. Instead the little inset area alone, needs shaving away around the laces.

This requires some careful work, but not near as much as very accurately carving away the whole convex surface minus the lacing, and doing that without the greater ease that the flat micro-rasp provided earlier, by arriving at a uniform fair surface without the lacing in the way.

A very small Veiner is used at the edge of each lace to indicate the lace holes and the edge of a needle file helps separate the laces without collapsing the short grain.

With the rugby ball completed some finessing of the various forms can be done with suitably shaped blades used as scrapers to tidy up and fair surfaces.

The next task now that all the main forms with their details are complete, is to tidy up the forms with scraping sanding and burnishing in preparation for the necessary fine finishing.

Even at this almost finished stage, sanding and other smoothing techniques will reveal a need to modify some parts of the carving. Smooth surfaces begin to reveal their true form, which may not be as fair as they first appeared, now that the camouflage of texture is removed. Tear outs will also become apparent and some surfaces may appear bland and in need of some interest by way of added detail.

The sanding process itself can degrade the crispness of sharp arises which will tend to cheapen the appearance of the work and design. A general rounded softness can develop during sanding, and if this happens it might be necessary to re-establish the clarity of the forms with edge tools again to bring back an all important crispness to the whole carving.

Having used sanding as a final shaping and blemish removal tool, together with scraping and some more work with edge tools, the work is now ready for fine sanding and polishing of all the forms with very fine grit abrasives in preparation for the final finish process.

It will not be practical to sand and polish every surface in a complex, deeply relieved design, but it is best to work ‘as if’ that is what you are attempting. Eventually even before the final finish with oil, (polyurethane or whatever) a good sheen will appear on all the more accessible parts of the carving.

It will not be practical to sand and polish every surface in a complex, deeply relieved design, but it is best to work ‘as if’ that is what you are attempting. Eventually even before the final finish with oil, (polyurethane or whatever) a good sheen will appear on all the more accessible parts of the carving.

The work will have a variable degree of polish and fortunately it is those parts that will reflect the most light that will have the hardest shine, helping to show the forms in the carving to their best effect. When the final finishing medium is applied to the timber, it is important that whatever sheen the medium imparts to the carving, it is best that it does not alter the variable sheen effect that has been obtained in the finishing prep. The variable sheen that models the forms by reflecting the light most from the highest points and also provides unblemished shadows in the lower areas.

A thickish, in this case a normal thickness coat of varnish, covering the carving will tend to pick up specular highlights in recesses, disrupting the overall modelling that describes the forms. For this reason the finishing medium needs to be extremely thin, merely accentuating the timber colour and grain, not forming a perceptible layer. An actual layer of finish would require an almost perfectly uniform, ultra fine sanding over every detectable surface or a very flat almost matt finish.

The carving has now been prepared for the final finish as described, however there is to be some gilding on parts of the lovespoon and in preparation for this the gilded areas are painted with acrylic ‘gold’ paint, a micaceous pigment combination that will allow a soft edge where the gold colour blends and gradually emerges from the timber. This paint will not tarnish or otherwise change and of course the overlay of twenty three carat gold leaf that is to be used will always retain its colour and provide a higher degree of brightness at the highest points.

With the areas to be guided prepared with suitable gold acrylic paint, feathered into the surrounding timber in some places, the final finish medium can be applied.

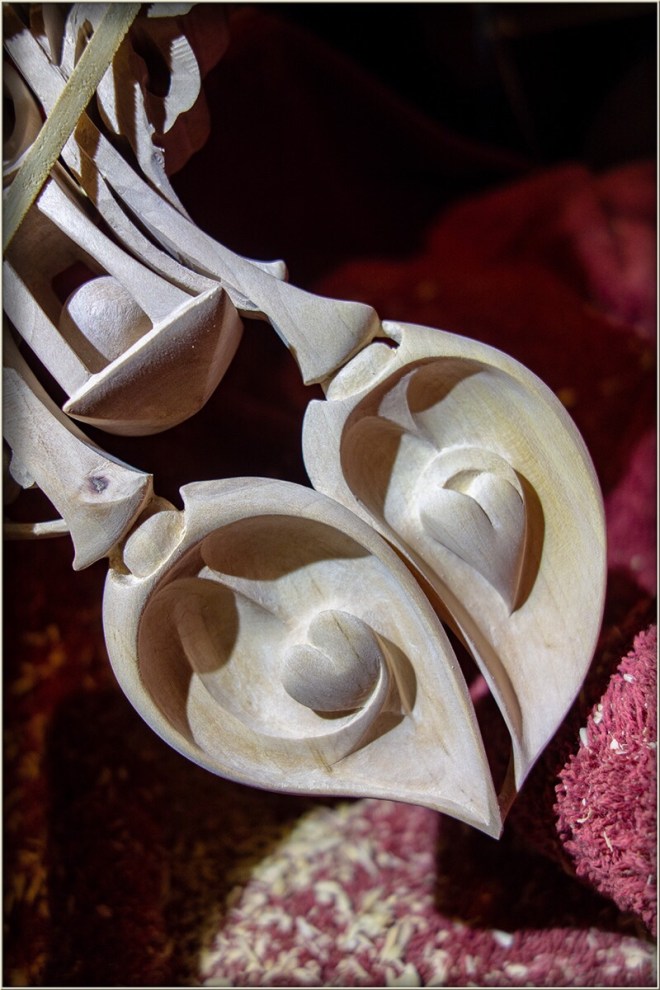

The gilding is to be applied to the two hearts and connecting swirls contained in the twin bowls, the very tip of the bowls and the connecting swirl tendril and the cords that bind the main heart motif in the centre of the lovespoon.

The finish medium is to be thinned polyurethane brushed over the carving and into the recesses and subsequently wiped off by brushing and wiping. The thinning of the polyurethane is achieved not with a measured proportional mix but by dipping the application brush occasionally in turps to thin the medium on the go.

The process is a continual, labour intensive one without a wait to dry phase. This removes any settling dust problems as the medium is continually moved over the surfaces distributing a very thin layer over and into every part of the carving. The process might be thought of as first trying to comprehensively penetrate and cover the carving with thinned polyurethane and then to comprehensively remove by brushing and wiping away ‘every’ trace.

An old tooth brush is useful for the dry-brushing of the medium in the deeper parts. In the later stages of the brushing/wiping off, the brush or cloth is dipped in a little Tripoli powder, also known as rottenstone brushed and wiped continuously as part of the wiping away stage. This working of the carving’s surface can continue until the whole carving feels dry to the touch and a pleasing sheen, even hard shine, develops.

The carving is now ready for the gilding of the hearts and cords. Transfer gold leaf is applied over those areas that will receive it by rubbing on the gold leaf over a slightly tacky layer of finish has been applied to those specific areas.

First the hearts receive their gilding , then the tips of the twin bowls. Then the cords binding the main heart.

The transfer gold is applied to as much of the area of the gilded features as possible but finally the gold leaf will highlight these features with the brightest gold effect at the high and middle points and the gold paint transitioning the gilding into the body of the carving.

With the gilding work complete a little glazing to accentuate the forms is carried out using some dark tan boot polish wax. This process can be carried out as part of one continual finishing session but in this case the work has been left overnight.

To use the boot wax it is brushed with a bristle brush or tooth brush, reserved for the purpose, liberally over the carving but particularly into the deepest recesses. It is important that the staining polish reaches all these areas, so the carving is examined closely from all angles to ensure every depth is reached. If necessary some turps can be added to the brush to wash the staining polish into deep cracks and fissures where the bristles cannot reach.

As with the application of the finishing medium this process can also be thought of as applying thoroughly and then, as if trying to remove every bit of it with a large polishing brush and cloth. A slight dampening of a cloth with turps can finally be used to remove all stain entirely from the highlights over the whole carving.

The final process in the finishing of the carving is to use a hard finishing wax. I have used the ‘traditional Wax’ product made by ‘U-Beat” finishes. On larger less deeply carved detailed surfaces I would use the “EEE’ (Tripoli) wax (by the same company) first before the traditional wax, but in this case the intricacy and depth suggested there would be little benefit in using it and there might be a risk of leaving a residue.

Buffing with a soft cloth brings the whole work to completion. The cloths used for the waxing and final buffing can be kept and re-used. However any cloths or rags that I have used with turps or oil, polyurethane etc I always place spread out, outside until dry and ready for the bin.

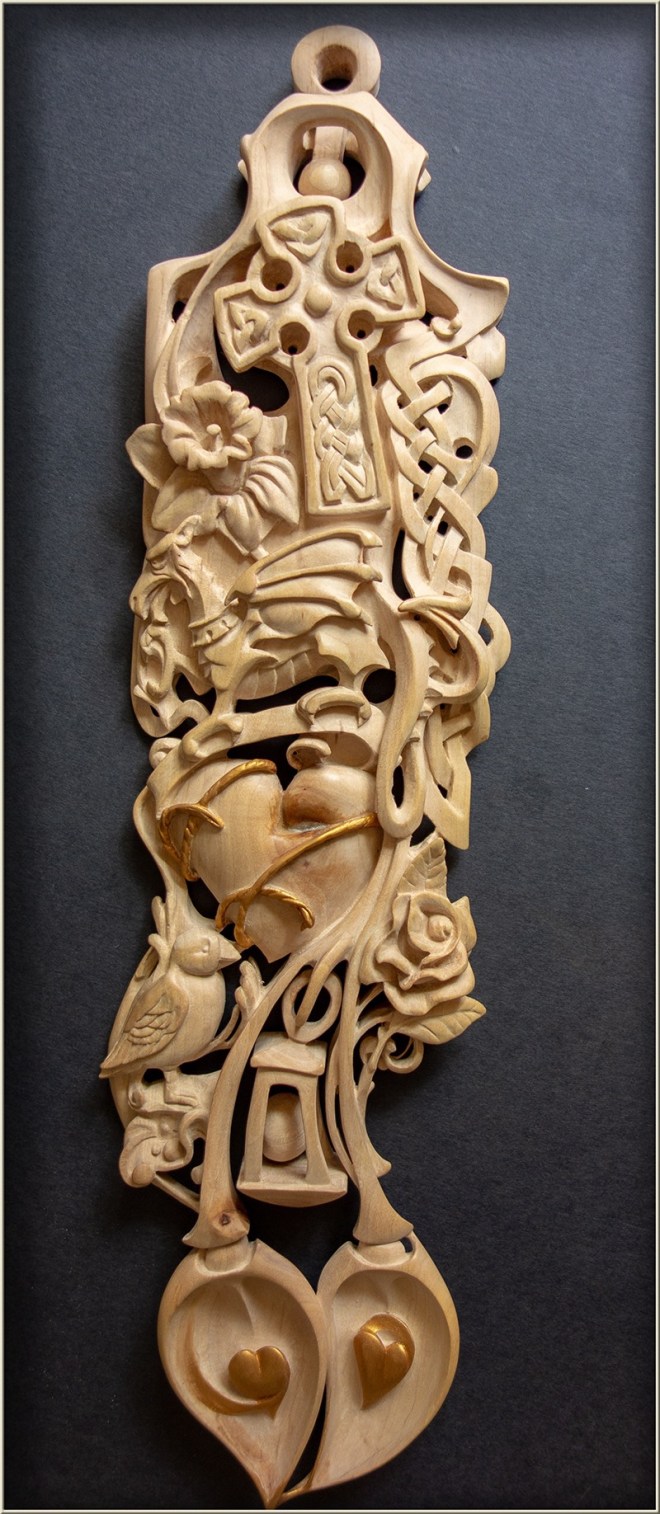

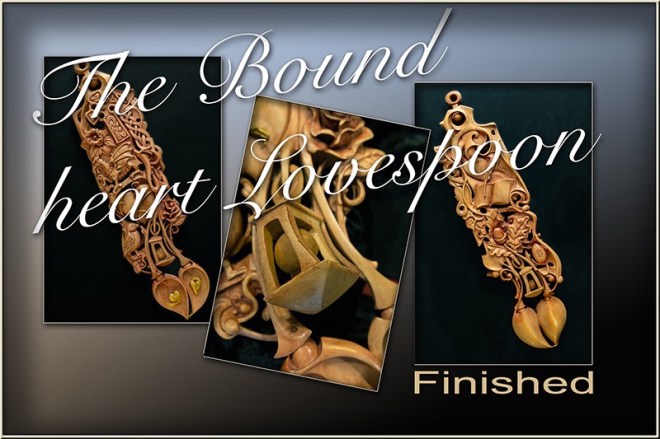

Here the ‘Bound-Heart Lovespoon has been finished ready for final photographing prior to packaging. The packaging itself is quite a process to help ensure a safe delivery. Postage is quite expensive from Australia an there is usually a bit of paperwork to be done for insurance, customs etc. For an overseas delivery a sturdy, rigid but light weight box with suitable fitted padding, is needed. For this lovespoon a purely functional plywood box was constructed to be quick enough to meet the deadline. On some occasions I construct a more finished frame/box intended for housing and displaying the lovespoon.

When photographing lovespoons I mostly use a black paper background with just a little light spilling onto the paper on one, usually the upper left edge, to show the paper texture. Daylight from a window is a useful soft light source for photographing carvings like this.

Crushed velvet, black in this case, also makes a useful background and I have used it here for these detail shots.

The necessary haste needed when photographing commissioned work due to be packaged and sent, usually results in rough and ready photography. Such is the case here. When there is time it is a good idea to go the ‘extra mile’ with the photography and use some more advanced techniques with specified intent.

A tripod can be used and then a more considered approach with lighting can be attempted. When using a tripod and if a good bit of time is available, stack-focusing in conjunction with suitable software, can provide photos that show sharp detail of the entire field of view.

Blur can present well also but a stack-focus result can show the work as it is meant to be seen, given that the lighting is directional enough to display the modelling and soft enough to reach into the depth of the forms. You don’t want it to look like a faint flat stain on a plank or like it has just been momentarily illuminated by a lightning flash in a horror movie. i.e. don’t use flash!.. A bit of motion blur due to not-quite-enough available light, would be better.

Another photography technique that can yield very good results, very specified, deliberate emphasis of featured detail, is ‘light painting’, the still life kind, not the line tracing in a night scene type. The two types have similarities but with a tripod and using layer and blending modes in a program like ‘Photoshop’ or perhaps ‘Procreate’. With a stack of identically positioned and focused long exposure shots from a tripod set-up, highlights can be ‘painted’ over the object with a small flashlight during a long exposure in dark or near dark. Selected parts from differently lit, but otherwise identical layers, can then be selectively and differentially combined into a result that emphasises detail and depth ‘to order’.

It requires time and the focused purpose of producing photos using these techniques however and that is often not possible and you have to make do with hand-held shots with a single light source from a window (very good) or whatever room lighting is available (hit and miss).

Most of the time I end up with window light or hit and miss techniques and it is only a few family-member-owned available lovespoons that have happened to be around during an ‘advanced photography mood ‘ that have received the advanced treatment.

For a partial silhouette effect, hand-held object (one hand) with hand-held camera (other hand) in bounced off the wall, available room-lighting can give you what you need for web use sometimes.

Provided some part of the image is sufficiently in focus a photo will be passable for use on the web.

But even then the light source needs to have the direction and quality to show the forms of the carving ‘in the right light’.

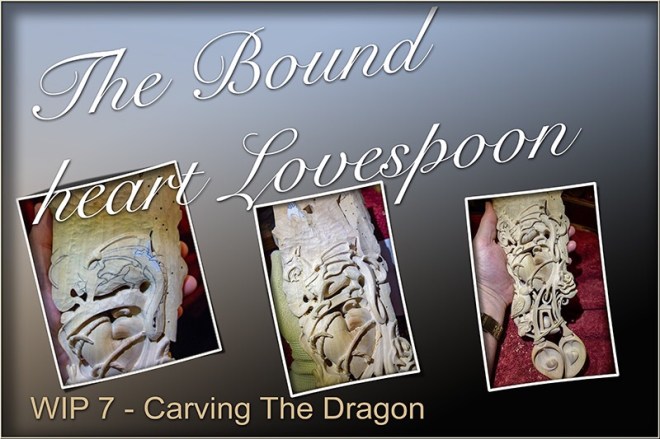

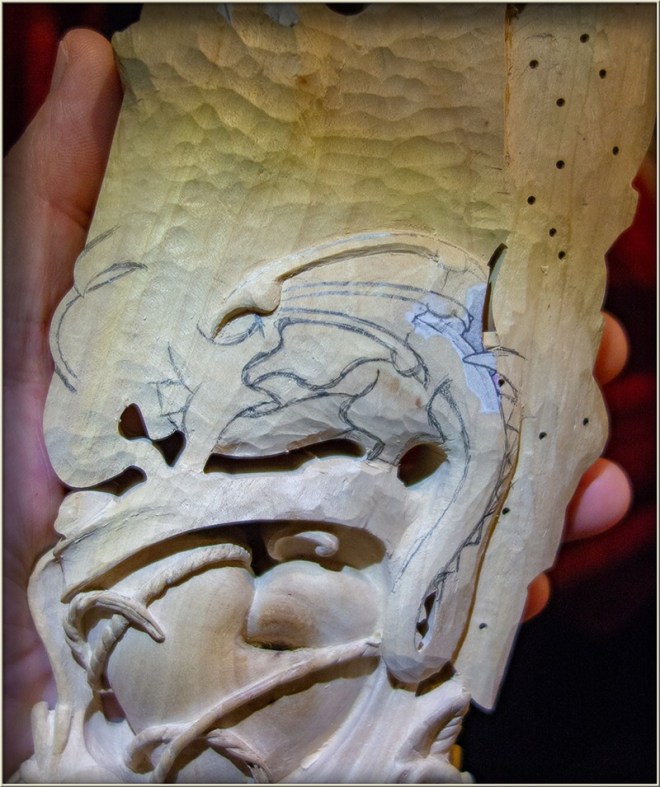

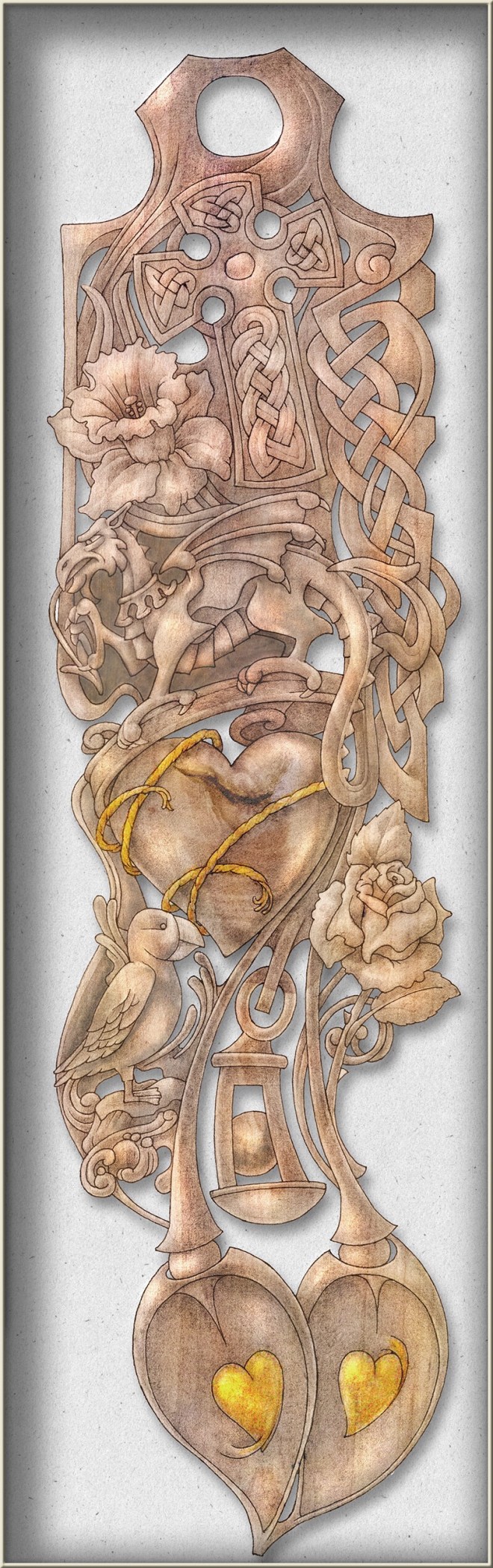

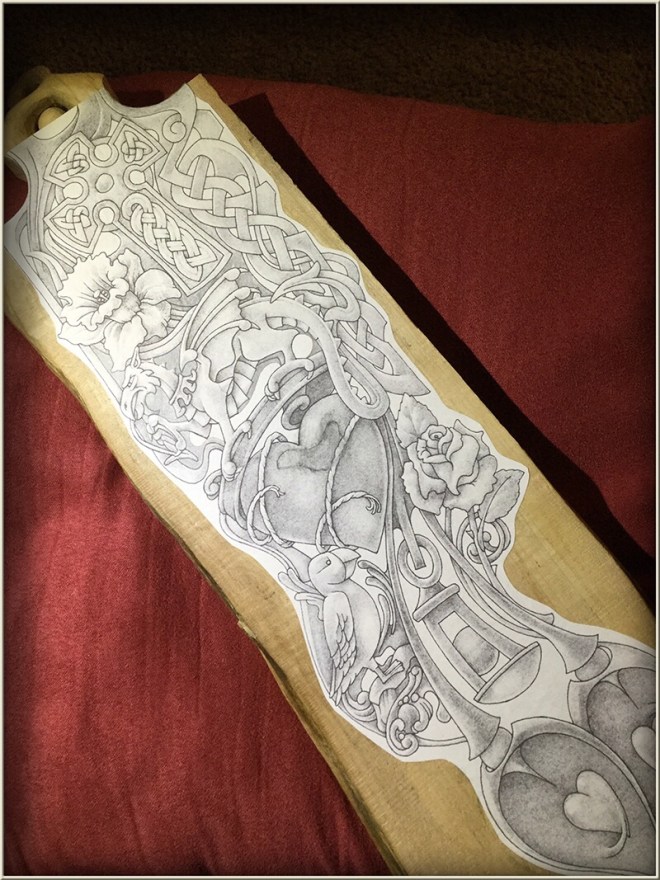

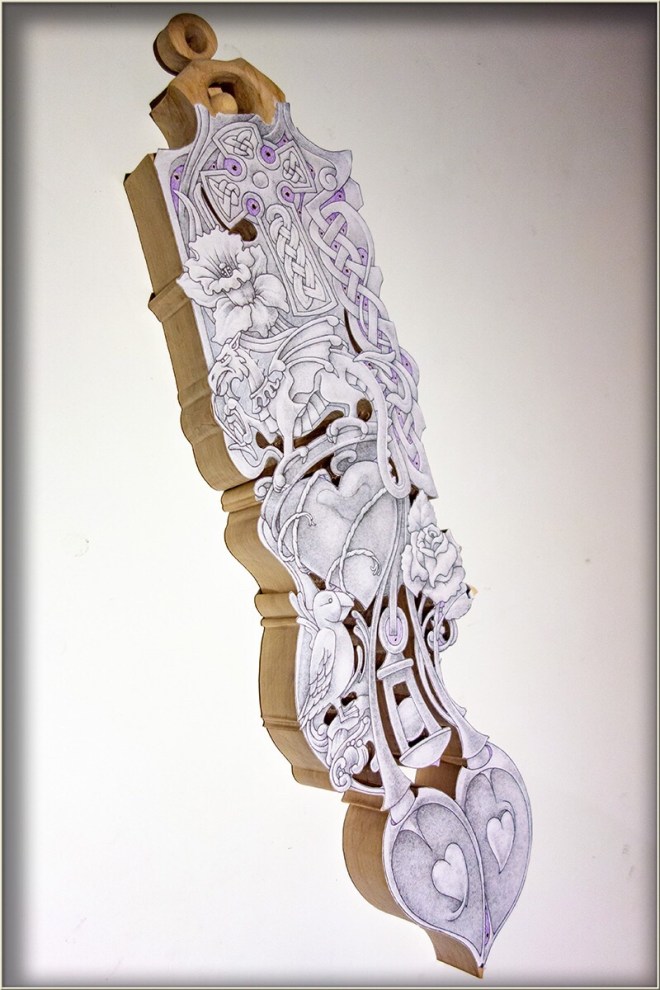

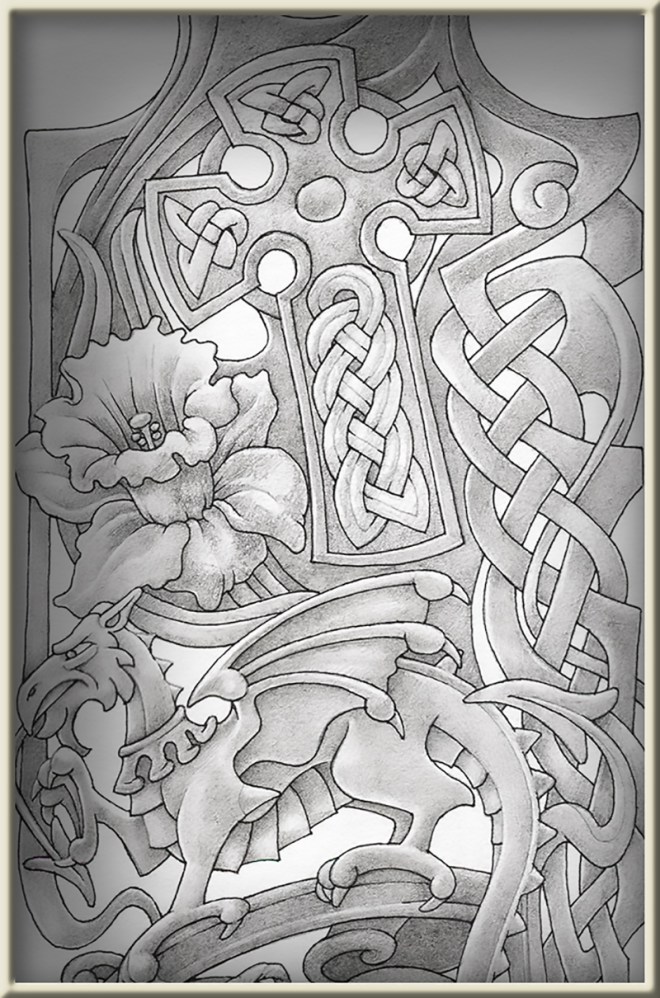

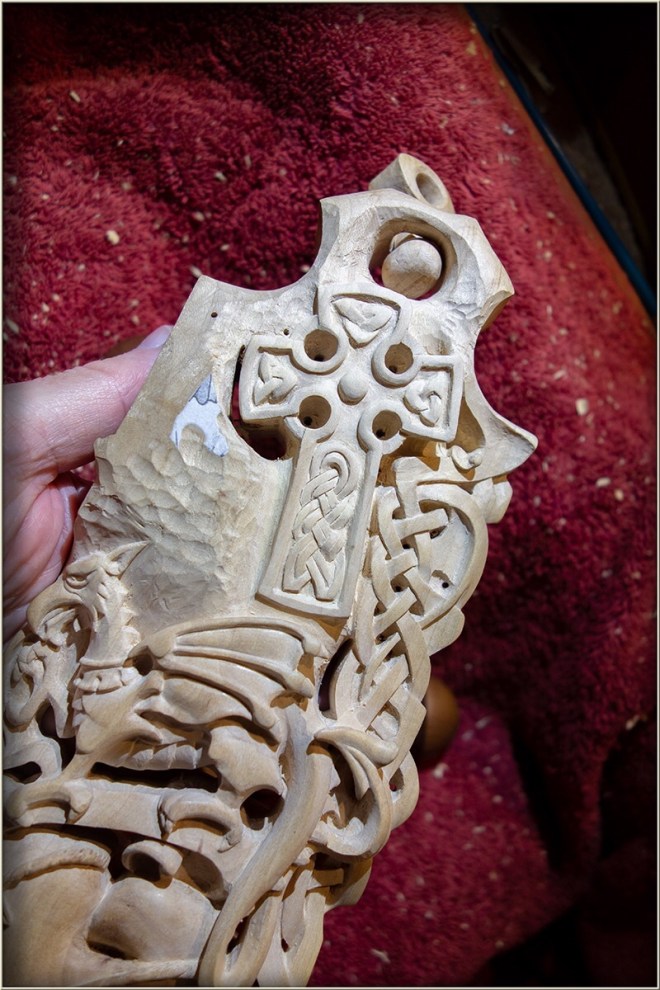

The Celtic cross, the daffodil and some unifying sculptural elements, in keeping with the art nouveau style adopted for this Lovespoon, are all the carved elements that remain to be completed on the front of the lovespoon. This will be the first time I have included the cross in any Lovespoon design. It is a Celtic Cross in this instance and together with the dragon and the daffodil, it signifies the Welsh heritage of the recipient.

The Celtic cross, the daffodil and some unifying sculptural elements, in keeping with the art nouveau style adopted for this Lovespoon, are all the carved elements that remain to be completed on the front of the lovespoon. This will be the first time I have included the cross in any Lovespoon design. It is a Celtic Cross in this instance and together with the dragon and the daffodil, it signifies the Welsh heritage of the recipient. It was as a teenager in 1965 on a QANTAS staff -travel trip my father had organised for our family, back to his birthplace at Llantwit Major, that I encountered the Celtic knot-work on Celtic crosses for the first time. The crosses were displayed at the ancient St Illtud’s Church and made quite a visual impression. During a couple of other trips to Wales much later I don’t recall seeing much in the way of Celtic crosses at all, but the earlier experience does lead me to easily associate these monuments with Wales.

It was as a teenager in 1965 on a QANTAS staff -travel trip my father had organised for our family, back to his birthplace at Llantwit Major, that I encountered the Celtic knot-work on Celtic crosses for the first time. The crosses were displayed at the ancient St Illtud’s Church and made quite a visual impression. During a couple of other trips to Wales much later I don’t recall seeing much in the way of Celtic crosses at all, but the earlier experience does lead me to easily associate these monuments with Wales.

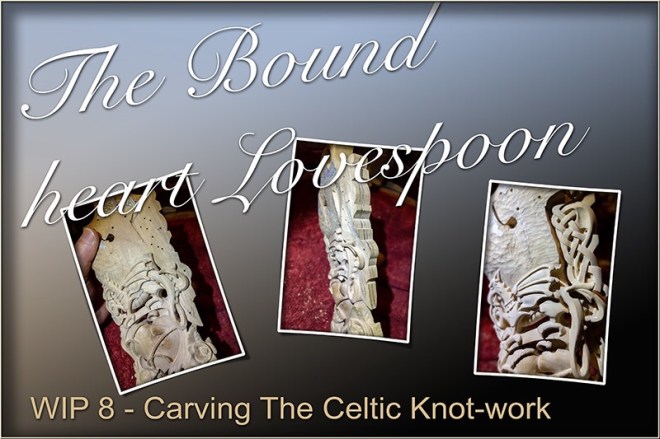

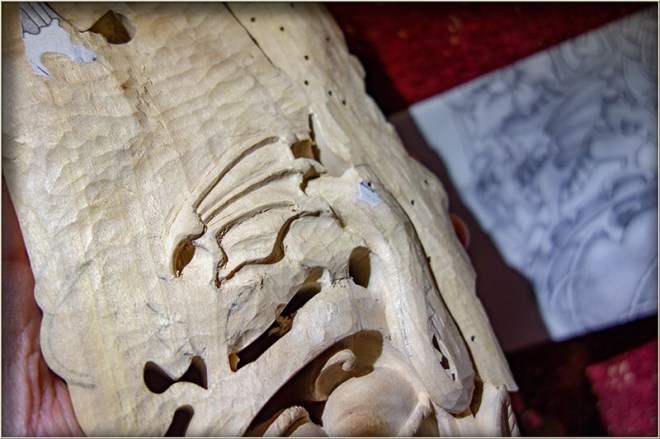

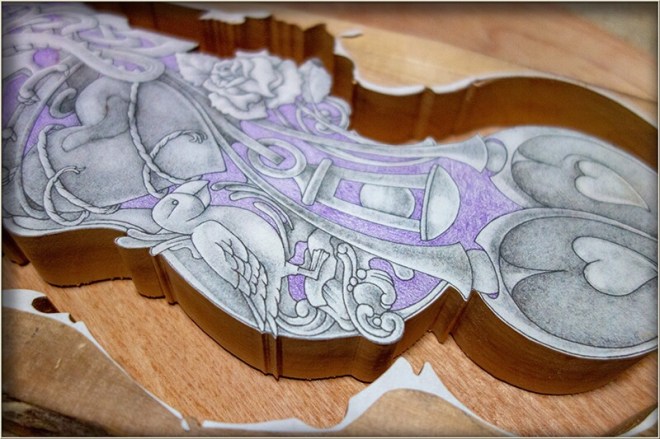

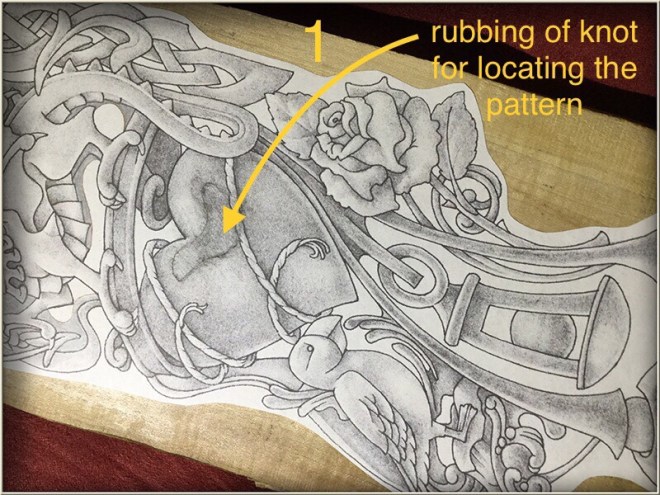

The form and orientation of the celtic cross motif on the lovespoon has been decided and its upper surface prepared for drawing in the knot work detail. The form of the cross is inclined slightly to the left and its long axis has a very slight curvature to the left. This is to maintain its relation to the slow serpentine curve along the axis of the entire design and in keeping with the general art nouveau style of the piece.

The form and orientation of the celtic cross motif on the lovespoon has been decided and its upper surface prepared for drawing in the knot work detail. The form of the cross is inclined slightly to the left and its long axis has a very slight curvature to the left. This is to maintain its relation to the slow serpentine curve along the axis of the entire design and in keeping with the general art nouveau style of the piece. The celtic cross in this design is comparatively small and so the decorative knot work cannot approach the complexity of the real thing. So it needs to be simple enough to carve at this size but still give a recognisable impression of a celtic cross. The knots at the top and sides are ultra simple and in the one with the longer knot work I have attempted to give an illusion of complexity by making it double stranded. A border around the perimeter is meant to add to this effect.

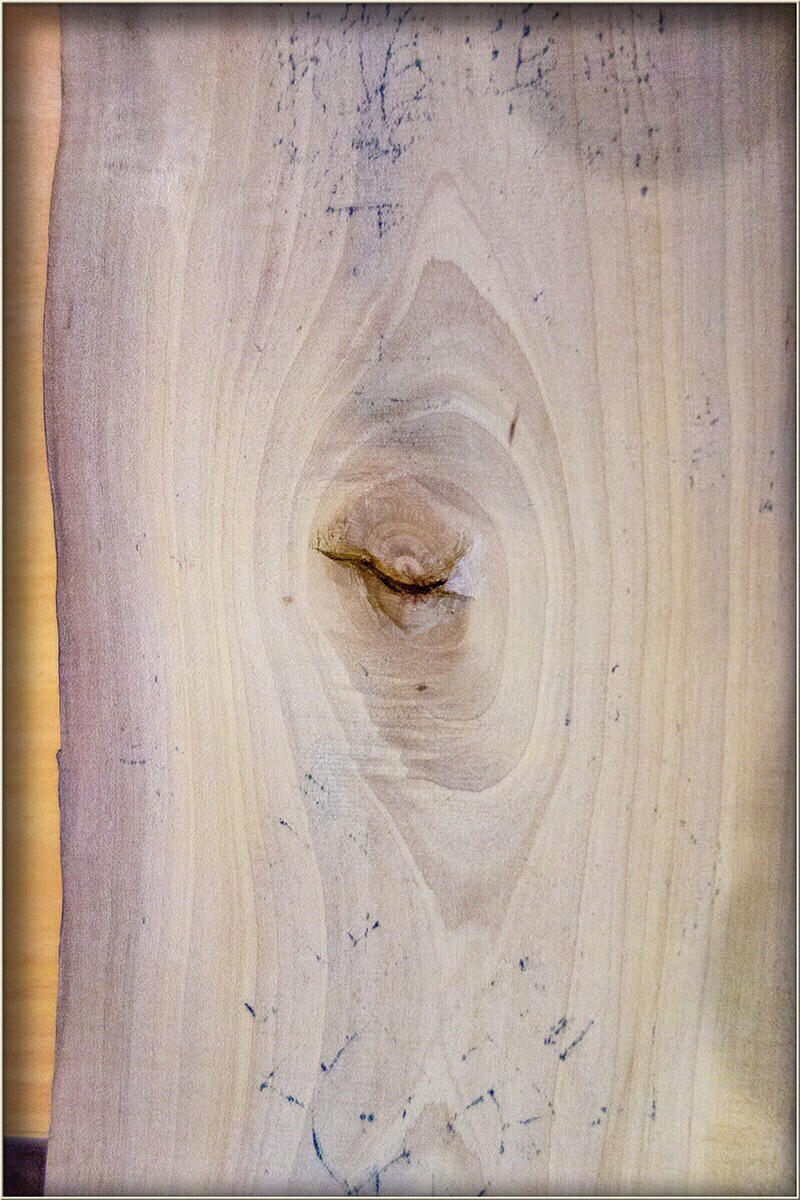

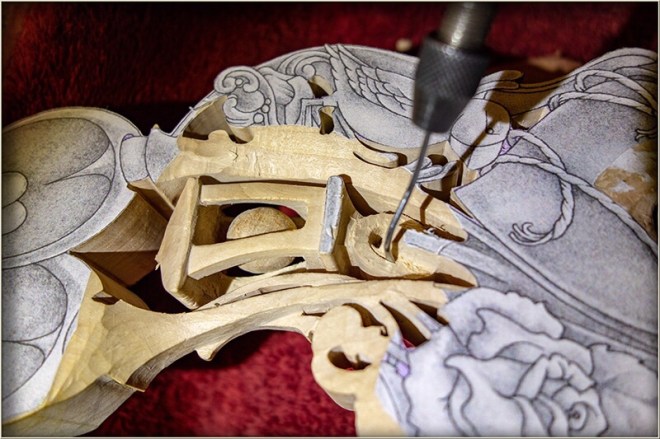

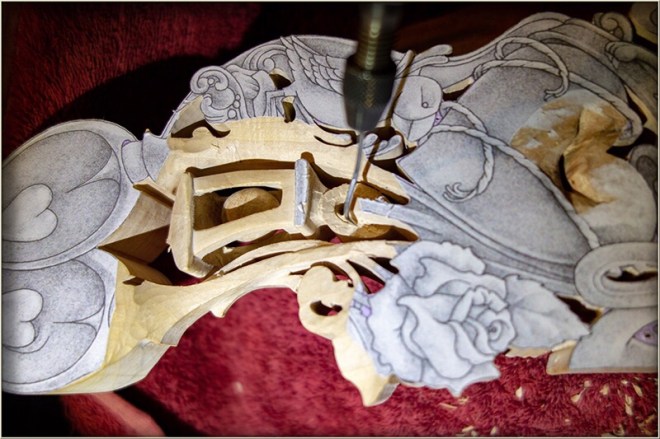

The celtic cross in this design is comparatively small and so the decorative knot work cannot approach the complexity of the real thing. So it needs to be simple enough to carve at this size but still give a recognisable impression of a celtic cross. The knots at the top and sides are ultra simple and in the one with the longer knot work I have attempted to give an illusion of complexity by making it double stranded. A border around the perimeter is meant to add to this effect. This Japanese maple timber has been very hard, as well as hard (tough) to carve but fortunately it holds detail well. The very narrow, in some places, areas that form the background to the decorative knot work can be deep enough to produce good shadow definition without compromising the integrity of the walls of the knot work and border. A bit of depth also allows for a very slightly domed effect on the background area for added visual interest.

This Japanese maple timber has been very hard, as well as hard (tough) to carve but fortunately it holds detail well. The very narrow, in some places, areas that form the background to the decorative knot work can be deep enough to produce good shadow definition without compromising the integrity of the walls of the knot work and border. A bit of depth also allows for a very slightly domed effect on the background area for added visual interest. Once these levels of cutting over the general form are established it is then just a matter of working the details to their completed form. The small micro chisels (shaped and sharpened music wire) accomplish most of this work, building depth slowly while handled with a pencil grip for fine control and naturally limited force.

Once these levels of cutting over the general form are established it is then just a matter of working the details to their completed form. The small micro chisels (shaped and sharpened music wire) accomplish most of this work, building depth slowly while handled with a pencil grip for fine control and naturally limited force. A small cranked bend in

A small cranked bend in  In the next post I will describe carving of the third typically Welsh signifying motif on this lovespoon, the daffodil.

In the next post I will describe carving of the third typically Welsh signifying motif on this lovespoon, the daffodil.